Fusion, The Ultimate Energy Source

As stable, reliable, cheap, and carbon-neutral energy supplies become an increasingly pressing issue, all eyes have been on nuclear solutions.

This includes nuclear fission, or the splitting of heavy atoms like uranium, thorium, or plutonium. This technology is making a dramatic comeback on the back of the phasing out of coal and gas power plants, despite the need for baseload power generation, as well as the trends of electrification of transportation, heating, and industrial production.

It is, however, not without problems, even for the more advanced 4th generation of nuclear power plants. Most notably, it still involves the handling of highly radioactive materials, something the public is still wary of and never going to be fully environmentally neutral.

This is why scientists have been looking at the promises of nuclear fusion, which merge together atoms like hydrogen, the same phenomenon powering the Sun.

Source: Nature

This would use a fuel that is the most abundant element in the Universe and produce only harmless helium or lithium. It would also be powerful enough to make available essentially infinite energy, with zero risk of explosion or runaway chain reaction.

The problem is that producing the required conditions is so hard to achieve that no fusion reactor has ever come close to commercialization so far.

This might change in less than a decade, at least according to Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS). The company has just announced that it is moving toward building the first commercial fusion reactor in Virginia.

CFS Reactor Project

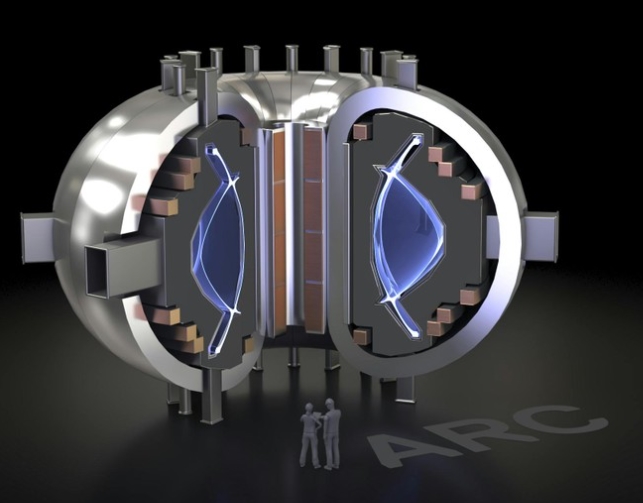

Commonwealth Fusion Systems is aiming for its ARC reactor to generate 400 MW for the Virginian power grid, which is enough to power 150,000 homes.

This is a radical advancement for the field of nuclear fusion, as it always seemed that the first scale-up reactor was 20-30 years away. Even the massive international endeavor that is ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) is not expected to be finished before 2039.

In comparison, the CFS reactor is planned to be built on a site owned by the energy company Dominion (D +0.2%). They see it as feasible as early as the early 2030s.

“Our customers’ growing needs for reliable carbon-free power benefits from as diverse a menu of power generation options as possible, and in that spirit, we are delighted to assist CFS in their efforts.”

Edward H Baine – Dominion president

Commonwealth Fusion Systems

CFS Technology

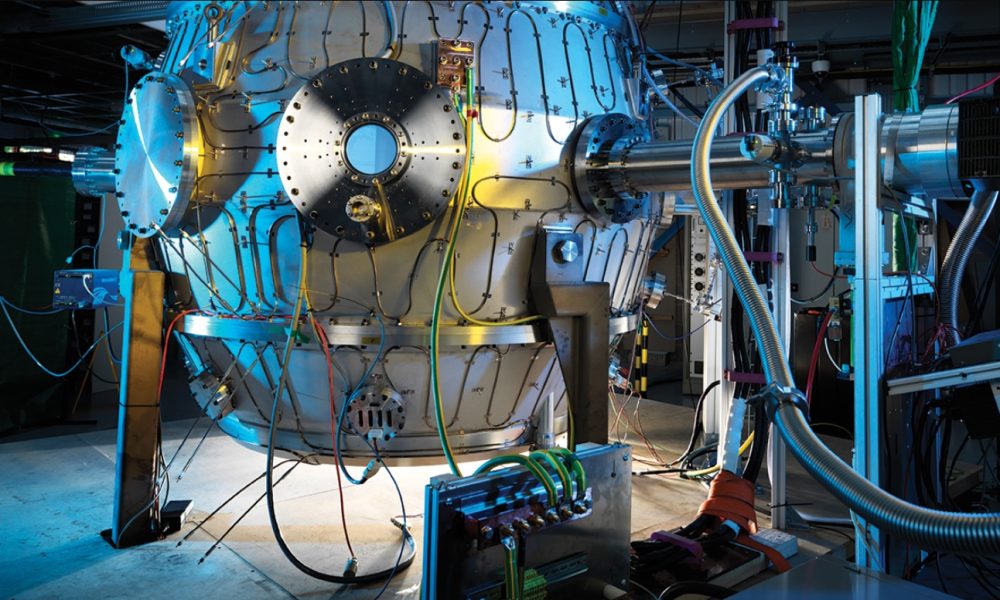

To understand how realistic this project is, we need to look at CFS history. The company was spun off MIT in 2018 and has raised $2B since, notably from Italian oil giant Eni. CFS is developing a fusion reactor based on the “classic” tokamak design, which forms a plasma in a torus (donut shape).

Source: DOE

(You can learn more about nuclear fusion and different reactor designs in “Nuclear Fusion – The Ultimate Clean Energy Solution on the Horizon” and superconductivity in “Progress In Superconductivity Making Way For A New Technological Revolution”)

CFS uses high-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnets developed in collaboration with MIT. They will control and compress the deuterium-tritium plasma to create nuclear fusion.

A liquid “blanket” captures that energy as heat, then transfers it to water that turns a steam turbine to generate power. Deuterium is available nearly everywhere and can be filtered from seawater, while ARC blankets will naturally produce tritium.

In 2021, it developed a 20 tesla HTS magnet, an improvement of 100-1,000x in previous magnet performance and the largest ever built.

These magnets are now assembled in a new, record-breaking design called the Central Solenoid Model Coil (CSMC). In 2024, the company also published its technology for a high-current-density, high-temperature superconducting cable that feeds power to these magnets.

The fuel usage will be very compact, like for all nuclear fusion technologies:

“Because only small amounts are needed, 30 years of ARC fuel can be delivered by a single truck when a new plant opens, with no price change risks down the line and no linkages to globally fraught supply chains.”

Upcoming Series Of Reactors

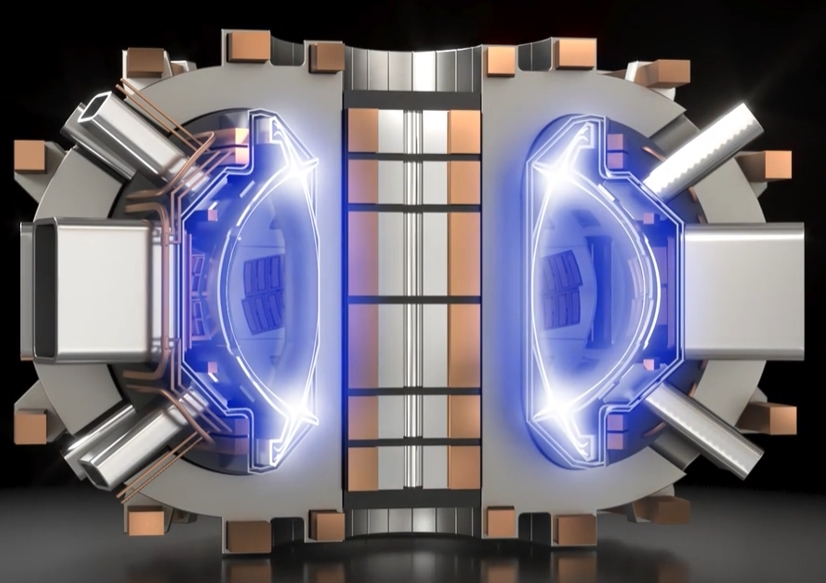

The HTS magnets will be used to build SPARC, aiming to be the first net-energy fusion reactor, meaning it will produce more energy from fusion than it consumes by igniting the hydrogen plasma.

SPARC is already in construction on CFS’s campus in Massachusetts but has yet to produce its first plasma.

Source: CFS

If all goes well with the SPARC demonstrator, ARC, to be built in Virginia is the next step.

Source: CFS

While SPARC is there to test the technology, ARC will be there to test the economics of the design. Each ARC will be about the size of a big-box store with about the same site needs.

Source: CFS

The next step is to mass-produce ARC, aiming to reduce manufacturing costs and spread out R&D costs.

Serious Endorsements

CFS is not only endorsed by Dominion and Eni but also by the UK Atomic Energy Agency, with whom it signed a five-year collaboration deal in 2022.

The research efforts of CFS were financed by awards from two US Department of Energy efforts, Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy (ARPA–E) and Fusion Energy Sciences (FES).

The MIT’s experts are also closely involved with CFS:

“Where the mission of the TFMC was to demonstrate a steady strength, the CSMC needed to demonstrate speed.

Hundreds of hands have touched this coil, from its inception on the drafting board to its long and complicated test program. The ingenuity, perseverance, and heart shown by this close-knit team was as impressive as the coil that sprang from their labors.”

Ted Golfinopoulos, one of the MIT Principal Investigators on fusion reactors.

Assessment Of CFS

Commonwealth Fusion Systems’ achievements in magnet technology are world-class. Stable magnetic confinement, the central concept of a tokamak reactor, could prove the missing key to solving the puzzle of nuclear fusion.

It is, in any case, going to be a very valuable technology, not just for fusion applications.

However, it is a little early to say how optimistic the CFS goals and timeline are. Nuclear fusion is a field littered with promising prototypes that have turned out to be less stable or productive than hoped for.

So, it is unclear if the extra power of CFS’ magnets will be enough to produce reliable, profitable fusion plasma.

As an example of possible unsolved issues, the tritium-producing blanket inside the reactor might not be as productive or durable as expected, even if plasma generation goes smoothly. Collecting back the power and turning it into electricity without damage to the reactor for decades of operation might prove tricky as well.

The confidence displayed by CFS and Dominion Energy, however, shows that nuclear fusion is making great progress. Together with AI able to develop new material or stabilize plasma in real-time, we might be just 1-2 decades away from unlimited cheap energy that would instantly allow for massively deploying desalination, space exploration, indoor farming, etc.

Fusion Companies

Currently, none of the companies dedicated solely to making nuclear fusion commercially viable are publicly listed. This includes Helion, General Fusion, Commonwealth Fusion, TEA Technologies, ZAP Energy, and NEO Fusion.

You can find an extensive list of startups in the nuclear fusion space on the dedicated page of Dealroom.

Still, one publicly-listed company has been active in the field of fusion, with a redirection of its concept from energy production to space propulsion: Lockheed Martin.

Lockheed Martin Corporation

Lockheed Martin Corporation (LMT +0.16%)

One notable exception to privately-listed startups dominating the field is the publicly traded company Lockheed Martin Corporation, a giant of the defense industry.

Lockheed used to work since the early 2010s on Compact Fusion, a nuclear fusion reactor it expected to be ready by the 2020s. However, it has since been announced that the work on the project was stopped in 2021.

The company has been very discreet about this project since the initial public announcement. To this day, it is unclear what could have prompted the company to abandon the idea.

At the same time, it seems that it did not fully abandon the concept, notably with investments in 2024 in Helicity, a startup developing a fusion engine.

The idea is to propel spacecraft with short bursts of fusion. Helicity plans to use a plasma gun, the same approach as General Fusion. Potentially, Lockheed’s internal results have shown that its design could not sustain fusion in a way that is compatible with energy production.

But maybe, at the same time, are short bursts enough for the need for propulsion in space and much closer to becoming an actual product? It would also be a better fit with the company’s overall aerospace and defense-focused profile.

You can learn more about Lockheed, including its main activity in weapon manufacturing, in a dedicated report from November 2024.